Pain, Hunger, Viral Fame: Inside China’s Wildest Survival Show

A farmer, a city slicker, and a welder walk into a mountain.

That’s the setup for China’s newest online obsession, a no-frills survival contest deep in central China’s Hunan province.

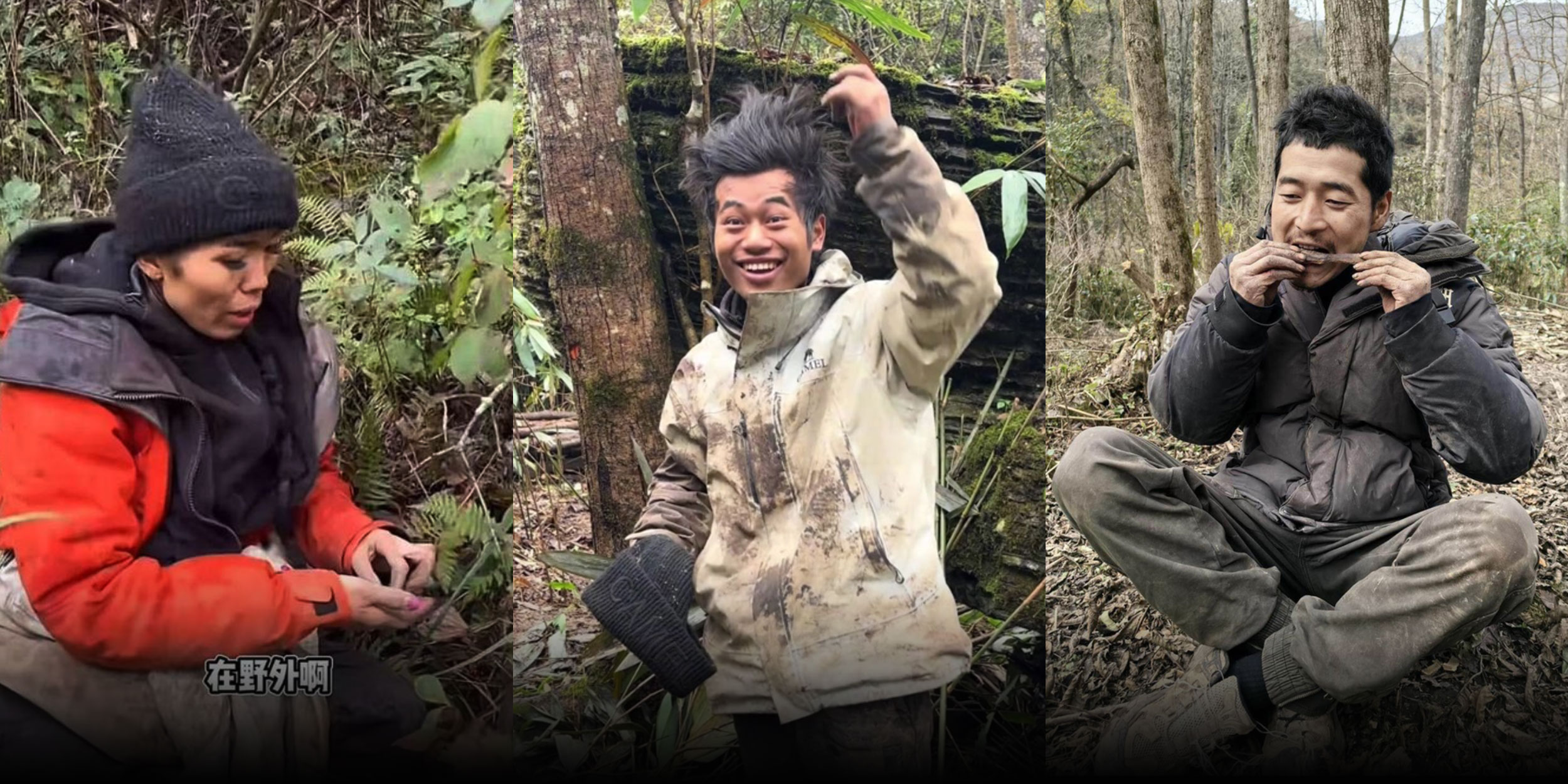

The unlikely trio is part of the “Qixing Mountain Challenge,” or “Camel Cup,” now in its second season, where 100 contestants are dropped into the rugged landscape of Zhangjiajie National Forest Park — the real-world inspiration for the floating peaks in “Avatar.”

Carrying little more than a machete, a basic survival kit, and a willingness to eat bugs on camera, they’re competing under a deceptively simple goal: outlast everyone else to win 200,000 yuan ($28,250). Now, only eight remain in the running.

Since the show launched Oct. 9 on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, clips of ordinary people shivering through cold nights, nursing failed fires, or celebrating a lucky insect catch have flooded social feeds, racking up hundreds of millions of views and turning the contest into one of the country’s most-watched spectacles.

Part of the draw is that nothing about the show looks polished. After years of filter-perfect social media feeds and tightly edited short dramas, audiences have swung hard toward huorengan — “real-person vibe,” Chinese internet slang for someone living an unfiltered, unscripted life.

“It’s something ordinary people can join,” explains Wang Yuxiong, director of the Sports Economics Research Center at the Central University of Finance and Economics. In a country urbanizing this fast, he added, many still feel a pull toward nature and the idea of testing their physical and mental limits, even if most never will.

“So when we see someone just like us step into the wilderness, we naturally project ourselves onto them.”

The frenzy has even drawn in local tourism bureaus, eager to ride the wave and fold hometown pride into the show’s sudden spotlight. But the attention has also spawned a rush of imitators. In the past few months, copycat survival contests have surfaced across the country, each promising its own version of the Qixing experience.

Many operate with bare-minimum staff and no clear safety protocol. And with winter creeping in, contestants in some events have been sidelined by frostbite, dehydration, or even malnutrition, raising questions about how far amateur survival shows can push the bar before crossing a line.

Into the wild

Huang applied for the second season of the Camel Cup the moment registration opened. After watching the entire first season, he felt the show was simply an extension of a life he already knew.

A 40-year-old farmer from a remote village in southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, he spends his days tending sugar cane and mango fields and filming rural routines off hours: salvaging fallen logs, carving nesting boxes for owls, and lifting the rescued birds back into the trees.

“The competition gave people like me a chance to show what we’re capable of,” Huang tells Sixth Tone. “I just wanted to see how far I could go.”

The October cold stiffened his hands, but he kept moving, stripping dry tinder from the forest floor and tracking the last light of day. For 17 days he lived in a shelter of bamboo and branches he’d pieced together from whatever the mountain offered.

“I grew up crossing creeks, gathering firewood, and identifying wild fruits,” he says. “These weren’t ‘survival skills’ to me, just everyday routines of mountain childhood.”

Still, before heading to Hunan, he spent days studying local vegetation because the edible plants there aren’t the same as back home. “You have to understand the land before you enter it,” he says.

So where others hesitated over what was safe to eat, Huang stood out as one of the best foragers on the mountain, especially at locating the region’s “wild trio” — yam, wild pear, wild kiwi.

“We grew up doing this,” he says. Instead of building just enough to get by, he furnished his camps with hedges and swings. “Life is your own,” he adds. “Even in the toughest circumstances, maintain your attitude and cherish the way you live.”

Yang Zhaoqin walked into the contest from the opposite direction — urban poise, manicured nails, and almost no experience with the kind of work the mountain demands.

By the end of her first week, the mountain had stripped all of that away from the 29-year-old shop owner from Yueyang, approximately four hours’ drive east of Zhangjiajie. Her training in cost engineering, and side gigs in AI, meant nothing in the wild.

Yang’s bamboo-and-wood shelter couldn’t hold back the rain. Nights left her soaked and shivering, and menstrual discomfort made even basic tasks harder. Still, she guarded her fire, moved into a nearby cave for safety, and learned to stretch whatever the mountain offered into calories: berries, wild greens, grasshoppers, murky water when she had no choice.

A native of the southwestern Yunnan province, she drew on childhood memories of foraging for mushrooms and soon began cooking with utensils she carved from bamboo. Each time the pressure spiked, she steadied herself with a mantra: “The more desperate the situation, the calmer I am.”

Viewers took notice. Clips of her shrinking frame and stubborn resolve spread quickly, and she became known online as “Cold Beauty.” She has since exited the contest, but as the last woman to leave, her arc remains one of the season’s most closely followed.

For Yang Xue, a 35-year-old welder from southwestern Guizhou province, surviving the wild was simply an escape.

“I’ve never really gone out to have fun. So this time, I just wanted to break away from my daily routine, enjoy myself, and lift my spirits,” he says.

Raised in a rural, mountainous area, Yang had some basic survival instincts, enough to build fires, identify wild plants, and get by without much gear. But Mother Nature still found ways to test him.

At times, he felt himself unravel, especially from the isolation. “There were moments I wanted to quit,” he says. “But I just kept pushing through.”

After 32 days in the wild, an eye injury forced him to withdraw. But instead of going home, he stayed on the mountain. He spent his days rebuilding shelters, experimenting with traps, and preparing for future competitions.

While climbing nearby mountains to train his heart and lungs after dropping out, he put it simply in a phone interview with Sixth Tone: “I fell in love with the survival game because the hunger made it feel real.”

Real deal

Across China, that appetite for the “real” has pulled in millions, including Liu Qian, a fan in her 30s from the northeastern Heilongjiang province who has spent the past month checking daily updates on her favorite contestants.

“I love the show because every contestant shows a different kind of strength. I see myself in them,” Liu says. She adds that watching them has changed her routines: she now cherishes simple things — food, clothing, basic comfort — and has cut back on shopping and the short dramas that once filled her evenings.

She admires Yang Zhaoqin’s composure in the wilderness, relates to Wen Cheche’s determination while managing a crushing mortgage, and delights in Zhang Bolin’s mix of resourcefulness and play. “Each of them reflects a piece of my own life,” she says.

Zhang in particular struck a nerve among young Chinese. The youngest participant, he arrived after a failed startup and months of burnout, hoping the contest might help him “start breathing again.”

On screen, the 25-year-old moved with an almost childlike joy, climbing trees, mimicking monkey calls, cracking one-liners, even befriending a family of wild rats he feeds leftover kiwi and calls his “neighbors.” Nicknamed “Lin Bei,” he drew a large following with his playful, exaggerated caveman persona.

For many viewers, the pull is a reaction to the hyper-curated personas that dominate China’s online platforms: performers in flawless makeup, staged spontaneity, the pressure to look composed at all times. The Camel Cup offers the opposite — ordinary people colliding with weather, hunger, and luck, with nothing to hide behind.

China’s familiarity with the survival format dates back to 2015, when “Survivor Games” — the local adaptation of “Man vs. Wild” featuring Bear Grylls — brought wilderness challenges to national attention. It was the first time many viewers saw survival packaged as entertainment, paving the way for today’s grassroots contests.

Earlier this year, the Camel Cup’s debut season took off when contestant Yang Dongdong lasted 70 days in the mountains, emerging nearly 16 kilograms lighter and 100,000 yuan richer. His raw clips — eating insects, fashioning traps, naming edible plants — spread quickly across social media and turned him into an unlikely influencer.

From Huaihua, also in Hunan, the 33-year-old now has more than 117,000 followers on Douyin, posting survival tutorials on catching crabs, trapping rats, and identifying wild vegetables. He also partners with his hometown tourism bureau, an early sign that the Camel Cup was becoming more than a game.

As the Camel Cup’s audience grew, local tourism bureaus and scenic-spot operators began appearing at Qixing Mountain to back their hometown contestants, folding regional pride into the show’s rising visibility. Contestants became inadvertent ambassadors, introducing viewers to local dishes, dialect jokes, and mountain trails that tourism departments were eager to promote.

None more so than Wu Gaoshu, better known online as “Miao King,” one of eight finalists in the competition still holding on.

Since November, Wu has become the centerpiece of social media content produced by the culture and tourism authority of Jinping County in Guizhou province, where his hometown is located.

When he mentioned missing his hometown’s rice noodles, local vendors filmed themselves cooking for him. When he spoke of wanting new clothes and medical care for his daughter if he won, county officials delivered outfits from a local factory and arranged treatment for her eye condition.

At the center of it all is Camel, the domestic outdoor-gear brand that outfits every contestant and lends the contest its name. As visibility climbed, Camel deepened its sponsorship, and applications for the third season have already exceeded 100,000 for just 20 spots.

Organizers are now weighing a year-round format, with the championship prize tentatively set at 500,000 yuan.

Thin ice

But in the wild, contestants admit, the stakes are much higher.

Huang learned this the hard way as temperatures plunged across the 1,400-meter slopes in October, his left leg stiffening and beginning to suppurate from frostbite. After losing four kilograms and deliberating for two nights, he exited in 25th place.

“I didn’t want to quit,” he says. “But staying could have made the frostbite far worse.”

As the contest wore on, several contestants developed serious health problems, including rapid weight loss, with some shedding more than 10 kilograms in a month, weakened immunity, skin ulcerations, and digestive disorders.

A midway medical check showed five participants with elevated potassium levels, and another was hospitalized for malnutrition. Anyone who fails the exam is immediately withdrawn from the competition.

And yet, across China, the format has spawned nearly a dozen new contests in recent months, each with its own scale, rules, and even all-female editions.

One event in Rongjiang County, in Guizhou, was shut down just days after it began on Dec. 2, following allegations of sexual assault against female contestants and reports that some participants had been secretly given food in violation of the rules.

Local authorities have opened an investigation and ordered full refunds; the event had charged 1,280 yuan per participant, attracted nearly 4,000 applicants, and selected 200 to compete.

Another event, the “Mulan Cup” in Yunnan’s Xichou County, was suspended three days before its scheduled start, with education and sports officials citing safety concerns amid persistent cold.

Elsewhere — in Henan’s Zhengzhou, southwestern Sichuan province’s Chengdu, and amid the northeastern Changbai Mountain range — unregistered survival challenges have appeared with little more than promotional posters, no confirmed routes, and no verified medical teams. Officials in several regions say they received no filings for the competitions at all.

And at the other end of the spectrum, some organizers, wary of injury or backlash, have relaxed rules so far that the “survival” looks closer to a weekend retreat. At a contest in Sichuan, participants can bring up to 10 tools, enough to permit surprisingly small comforts like brushing their teeth each morning.

Wang Yuxiong, of the Central University of Finance and Economics, warns that the unregulated boom in high-risk competitions endangers not only participants but the credibility of the entire outdoor sports sector.

“Professional guidance, proper risk assessment, and clear regulations are essential,” he adds. “Not just to prevent accidents, but to ensure the sustainable growth of outdoor sports.”

But even with organizers coordinating medical support, 24-hour rescue teams, evacuation routes, and safety inspections before contestants enter the game, the risks remain unpredictable.

On one occasion, a contestant was caught in a sudden downpour, soaked to the bone and shivering uncontrollably, Huang recalls. Trained in emergency response, he rushed over after hearing a whistle for help, opened the contestant’s survival kit, wrapped him in a thermal blanket, and assisted the medical team in evacuating him.

“These moments remind you how thin the line is between a contest and real danger,” Huang says.

Back atop Qixing Mountain, a handful of contestants still tread that line as the Camel Cup enters its final stretch: eight people scattered across the cold ridges, and a country watching to see how far they can go.

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Contestants take part in the “Qixing Mountain Challenge,” also known as the Camel Cup, in Zhangjiajie, Hunan province. From Douyin)